On Friday, the U.S. State Department released its Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the proposed Keystone XL pipeline. Its central finding—that the project would have little impact on climate change—was a disappointment to many in the environmental community. After all, the project would bring dirty oil from the Alberta tar sands (see above) to the Gulf Coast of the United States and clear the way to an even more carbon-intensive energy future for the U.S. Back in June, President Obama pledged not to green-light the project unless it was found by the State Department not to “significantly exacerbate the problem of carbon pollution.” Some viewed Obama’s punting of the issue to Kerry as a good sign for pipeline opponents, while others viewed it as shrewd posturing. Now with the cat out of the bag, those who were suspicious of Obama’s stance are looking pretty smart.

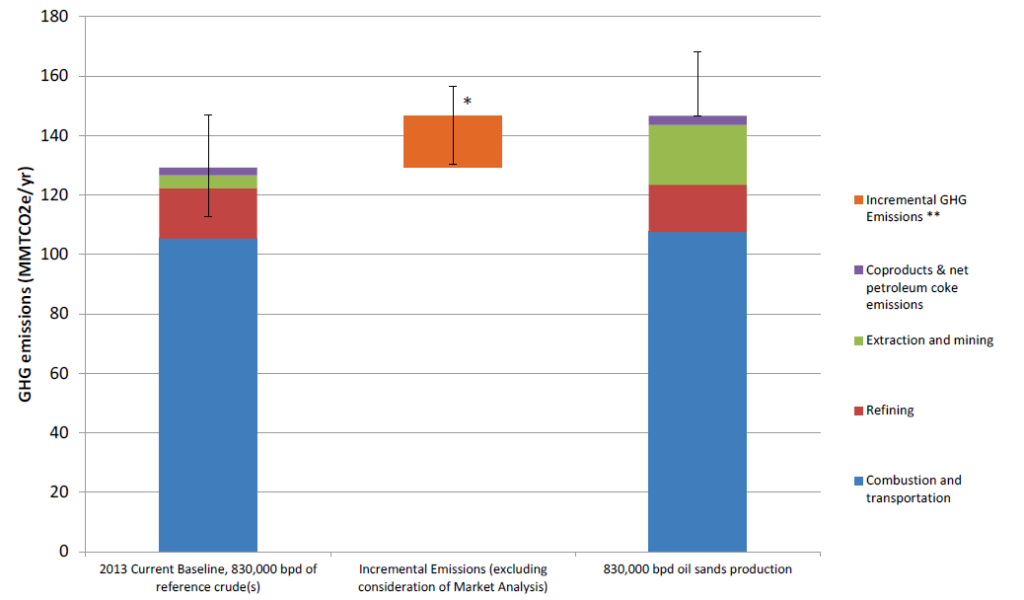

But what gives? Isn’t it “bad” to facilitate demand for a dirtier commodity than what we currently use, much less the much cleaner non-fossil transportation fuels of the future? From one perspective, the ability to extract this oil is a marvel of modern technology—engineers wouldn’t have been able to even get at the stuff just a few years ago, before technology enabled its extraction from the thick tar sands. Seen differently, the need for advanced machinery to extract each barrel of crude adds significantly to its life-cycle carbon footprint. The EIS acknowledged the added greenhouse gas (GHG) burden of heavy tar sands crude relative to the lighter crude we generally refine in the U.S. today. In picture form, here’s what the difference looks like:

In State’s words, here’s an idea of what these extra emissions amount to:

“The range of incremental GHG emissions […] for crude oil that would be transported by the proposed Project is estimated to be 1.3 to 27.4 MMTCO2e annually. […] This is equivalent to annual GHG emissions from combusting fuels in approximately 270,833 to 5,708,333 passenger vehicles, the CO2 emissions from combusting fuels used to provide the energy consumed by approximately 64,935 to 1,368,631 homes for 1 year, or the annual CO2 emissions of 0.4 to 7.8 coal fired power plants.”

Make no mistake about it—we’re talking about an especially polluting kind of oil here. State never could have credibly denied that fact. So State’s ultimate intimation that Keystone XL wouldn’t have a significant impact on climate (though the report is pretty careful to avoid making such a definitive statement outright) is therefore a question of what it’s been compared against.

In its analysis, the State Department assumes that if the Keystone XL petition is denied by the President, the tar sands oil—all 830,000 barrels per day of it—will simply find other ways of getting from point A (Alberta, though technically the tippy top of Montana) to point B (the Gulf Coast, though technically Nebraska or Oklahoma, where it can link up with existing pipes for the rest of the journey). In the pipeline’s absence, the report explores several “no-action alternatives” that involve some combination of rail and tanker transport of oil either directly to the Gulf Coast or to the existing pipe beginning in Oklahoma. The emissions from constructing the pipeline are dwarfed by the greater greenhouse gas releases from operation of any of the no-action alternatives, which require lots of fuel to transport the oil. By contrast, Keystone would require comparatively little fuel to operate. Looking at these alternatives, it’s easy to say that a pipeline makes the most climate sense.

But at the end of the day, as with most large-scale analyses, it’s all about assumptions. Embedded in the EIS analysis is the assumption that the Gulf Coast will get all of the oil the tar sands have to offer somehow. The market assessment deems it unlikely that the denial of Keystone’s petition would impede extraction efforts in Alberta. Even if this is true, how likely do we think it is that all 830,000 barrels per day make it to the Gulf Coast without the help of this pipeline? It’s difficult to assign a value here, admittedly, but State really ought to try. Because unless it’s a proven certainty that all the oil makes the trip regardless, the emissions from the no-action alternatives should be scaled by this probability to give us an idea of the expected value of emissions. For what it’s worth, a likelihood below about 80% begins to tilt the scale in favor of alternatives.

Without an extensive and efficient pipeline with pretty low operating costs, it would become pretty costly to get one’s hands on tar sands oil. And the U.S. isn’t short on other options, at least not yet. Why would we still insist on getting our oil fix from Alberta in such a scenario? If the tar sands oil flows without having Keystone as its outlet, I’m guessing it goes to other countries. To me that means that less than 80% of full-scale tar sands production would end up in Gulf Coast refineries without Keystone.

Secretary of State John Kerry now faces the decision of how to interpret this report, and ultimately how to act on it. He could take his chances that tar sands oil production would falter without the pipeline to prop it up, and opt to reject the petition. But now that the EIS has materialized, Kerry can’t take an overly activist stance that would undermine his own department’s credibility. More likely is that Kerry is bound by State’s assumptions regarding ugly no-action alternatives, and approves the petition. And maybe that won’t be the end of the world; some have suggested that Keystone opposition is a costly way to spend scarce political will for the environmental cause anyway.

I’m guessing we’ll get the chance to find out.

Crosspost from The Big Word Blog.

The banner image features the Syncrude Aurora tar sands mine in Fort McMurray, Alberta. The image is courtesy of Greenpeace/Jiri Rezac.