Many of us at ERG wonder why there continues to be electricity waste and resource waste, despite available solutions. You can hear the aghast complaints around the lunch table: “Why don’t people set back their thermostats?!”, or “Why don’t restaurants compost?!”

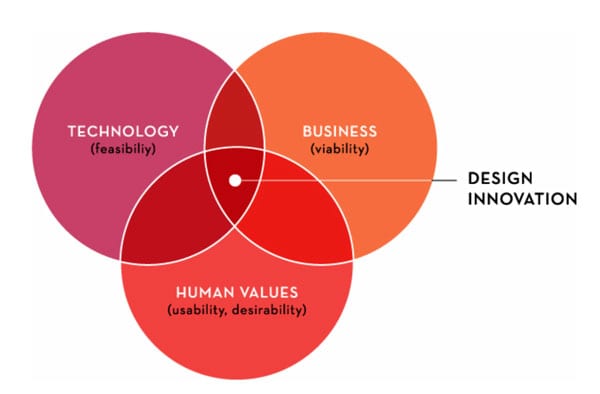

Design Thinking (or Design Innovation) is a helpful framework to assess the possible barriers to the solution. It inspects whether the solution is desirable, feasible, and viable. Failed ‘solutions’ often lack one of these attributes. It gets a different name when it is applied to different domains. When creating physical products, it is called Product Design; developing services – Service Design, presenting information – Visual Design, and shaping organizations – Enterprise Design.

This framework can also be helpful for tasks in graduate school less formidable than global sustainability, like applying for a grant, shaping a student organization, or teaching a class. We apply a type of Design Thinking when writing an NSF proposal. We apply Visual Design to tailor our essays for the end-user: the tired, overworked reviewer traveling on airplane.

But what is Design Thinking? Let’s break this buzzword down. Design Thinking is an over-arching method for innovating or problem solving. The idea is to simultaneously consider an idea’s desirability, feasibility, and viability. Desirability is the human desire for the solution because of its aesthetics, functionality, or ergonomics. Feasibility is that the idea is possible with current technology and regulations. Viability is that the solution can be implemented economically. The focus on all three distinguishes this strategy from other approaches like ‘technical solutions’ or ‘continuous improvement’, which focus on just feasibility or miss desirability.

I’ve found that Design Thinking leads to more effective and elegant solutions. I first witnessed it when I took a capstone course in Product Design, manufacturing a bee hive monitoring device that was proposed to Shark Tank’s initial screening. (Spoiler alert, we didn’t get on the show.) I further saw Design Thinking’s benefits during consulting when I helped create a custom rebate program for a utility and helping launch a website and digital tools for an energy efficiency start up.

Now, a primer on the actual methodology. I like to put it into three steps:

- Problem Framing

- Divergent Thinking

- Convergent Thinking

We’ll use programmable thermostats as an example of how to use each step. It seems that until recent smart thermostats, even the most conscientious and skilled of us would rather keep our house heated constantly at 80 degrees than dare interface with that mean robot box that seemed to taunt any attempt at a change in temperature schedule.

Problem Framing:

First, the designer or problem solver must frame the problem that is to be solved. There are three sub-steps to framing the problem. Identify and Empathize with End User The first and most fundamental step is identifying who the end-user is that has a need for a problem to be solved and putting yourself in her shoes. Hint, it is usually a human (though there is plenty of product design for cats). This is where you’ll hear the term “Human Centered Design.” This is the distinction that Design Thinking puts the problem in the frame of reference of the human end-user not in the frame of reference of the designer, the engineer, or the piece of technology.

In our case, the end-user is the everyday inhabitant, Gertrude. She is not a dedicated environmentalist and not a computer coder. To empathize you think about the long days she has at work or the frustrating spontaneous errand days and the last thing she wants is for her house to be cold just to save a couple bucks on energy. Setting a thermostat schedule is so low on the chore list. Define the Problem This is also known as “The Need.” This is a very difficult step. It is the classic of identifying the disease not the symptom. In our case it is rather simple, Gertrude wants a comfortable house whenever she is home and to save energy when she is not, even with a capricious schedule. Establish Constraints These are often broken down into the technological, the economical, the ergonomical, and the cultural. What is physically possible with current technology? We don’t have technology yet that can read our minds and determine exactly when the temperature is too low or too high. What are the cost or lead time thresholds for the product? Most people aren’t willing to spend $1,000 on a thermostat. What human physical limitations must we work within? It must be comfortable (physically or cognitively) to adjust temperature settings. And finally, what taboos or traditions should we be cognizant of? Design should probably avoid a fire-engine red to fit into the typical interior design of a house.

Divergent Thinking: create choices.

This is where the classic brainstorming comes in. No thought showers. Serious, heavy brain storming.

This is not the time for critique. We need to generate as many ideas as possible. Weird ones, too. Out-there ideas bring in aspects or relationship we wouldn’t have otherwise imagined. The ‘quality idea’ at the end is a function of the quantity of ideas earlier.

When teammate Randy suggests the thermostat that should be a big lever that comes out of the wall with a stress ball at the end, hold back the giggle or sigh and write it down. On to the next idea. Randy’s idea might inspire others to consider other ideas that only have one interface point.

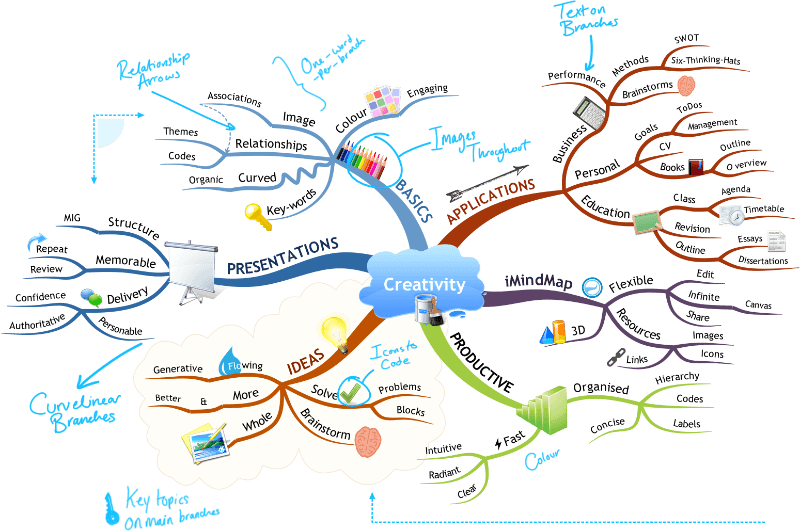

Convergent Thinking: make choices.

This is where you start paring down ideas.

You can use mind maps, decision matrices, and prototypes. The key here is to fail early and often. This is where you’ll hear the term “rapid prototyping.” *Heads Up* A common mistake is to invest too much into a prototype. First prototypes should look stupid – cardboard, pipe cleaners… childish. Often people pour too much time and resources into a prototype, which detracts from materializing other ideas. This makes the creator personally invested in that single prototype, often making them more defensive and less willing to consider other options.

Maybe to appease Randy you take a dowel rod and stuff a stress ball on the end and hold it next to the wall and show how this really won’t fit well behind a couch or below a family painting.

In the end, if executed well, the Design Thinking process can lead to elegant and effective products like the new smart thermostats we see that can be adjusted by a smart phone app or have few minimal physical buttons to get confused over.

If you want to learn more about Design Thinking, the umbrella group on campus for Design Thinking is the Jacobs Institute. You can find info on student groups, classes, seminars, and tools there. Another main resource is the D School at Stanford where much of Design Thinking originated from. You might even apply Design Thinking to your life! (Yep, you can take a class at Berkeley on it. Some ERGies are doing it this semester.)

Additional images from Capterra, iMindMap and Alam and Shakil (2014).