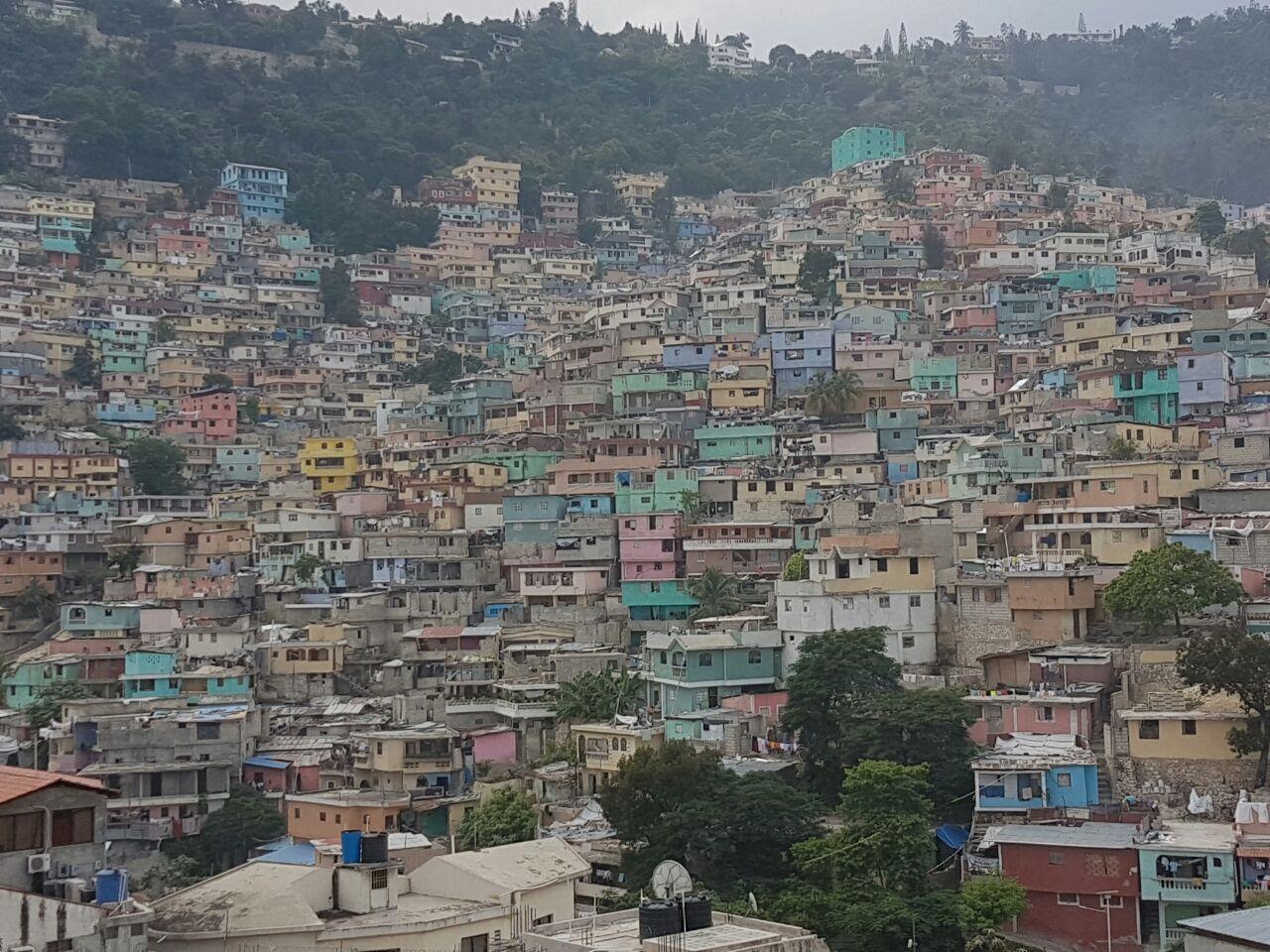

Killick Stenio Vincent neighborhood in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Photo by Jessica Kersey.

Rapid urbanization triggered by economic development was a defining global phenomenon of the 20th century.1 In many cities of the Global South, the rate of urbanization quickly outpaced the ability of local governments to cope with the demand for affordable housing.2 Millions resorted to building homes on land to which they had no legal claim, resulting in the densely-populated, low-income neighborhoods we see in cities like Mumbai, Dhaka, and Port-au-Prince.

In 2019, the United Nations estimated that the total population of people residing in so-called informal settlements or slums exceeded 1 billion.3 In sub-Saharan Africa, an estimated 60% of urban residents live in slums.4 Furthermore, urbanization rates show no signs of slowdown in the coming decades given the drivers of population growth, rural-urban migration, and displacement of rural populations from conflict, natural disasters and climate change.5 By 2050, an estimated 70% of the world’s population will reside in cities, with the corresponding slum and informal settlement population growing to 3 billion.6,7 Given that the majority of this growth will occur in developing cities which lack the technical and financial resources to accommodate these new low-income populations, providing adequate and equitable basic services to these under-resourced urban areas will be an enduring challenge for decades to come.

These settlements go by many names around the world, including slum, shantytown, bidonville, barrio, favela, and urban village, each of which carries particular social, historical, and linguistic particularities. However, academics and practitioners have struggled to find a common conceptual framing by which to categorize and understand these areas, which show tremendous variation in physical, legal, economic, and political conditions within even a single city.

The term informal settlement has become a catch-all term to describe communities that have formed outside of the legal planning process, but this lacks conceptual nuance as it addresses only one characteristic (legality) of a layered socioeconomic, political, and physical situation. In 2003, UN-HABITAT introduced a more robust definition for a slum as having one or more of the following characteristics: inadequate access to safe water, inadequate access to sanitation and infrastructure, poor structural quality of housing, overcrowding, and insecure residential status.8 Despite this definition’s widespread use, many have denounced it as stigmatizing and as promoting colonialist Euro-American urban planning paradigms which place undue focus on notions of “formality.” As Alan Mayne, the author of Slums: A History of Global Injustice argues: “Usage of the word ‘slums’ is profoundly deceitful; it’s a word that has been used by powerful groups to stereotype, marginalize, and disempower.”9

Conceptually as well as ethically, these terms fall short of providing a robust framework with which to understand and discuss these urbanization trends. A slum need not be informal if it has been granted land tenure by the local government, and an informal settlement may not be a slum depending on the quality of construction and living conditions. Furthermore, though it is implied that both informal settlements and slums are home to the urban poor, some of these communities (notably, several of Brazil’s favelas) have given rise to a burgeoning middle class.10

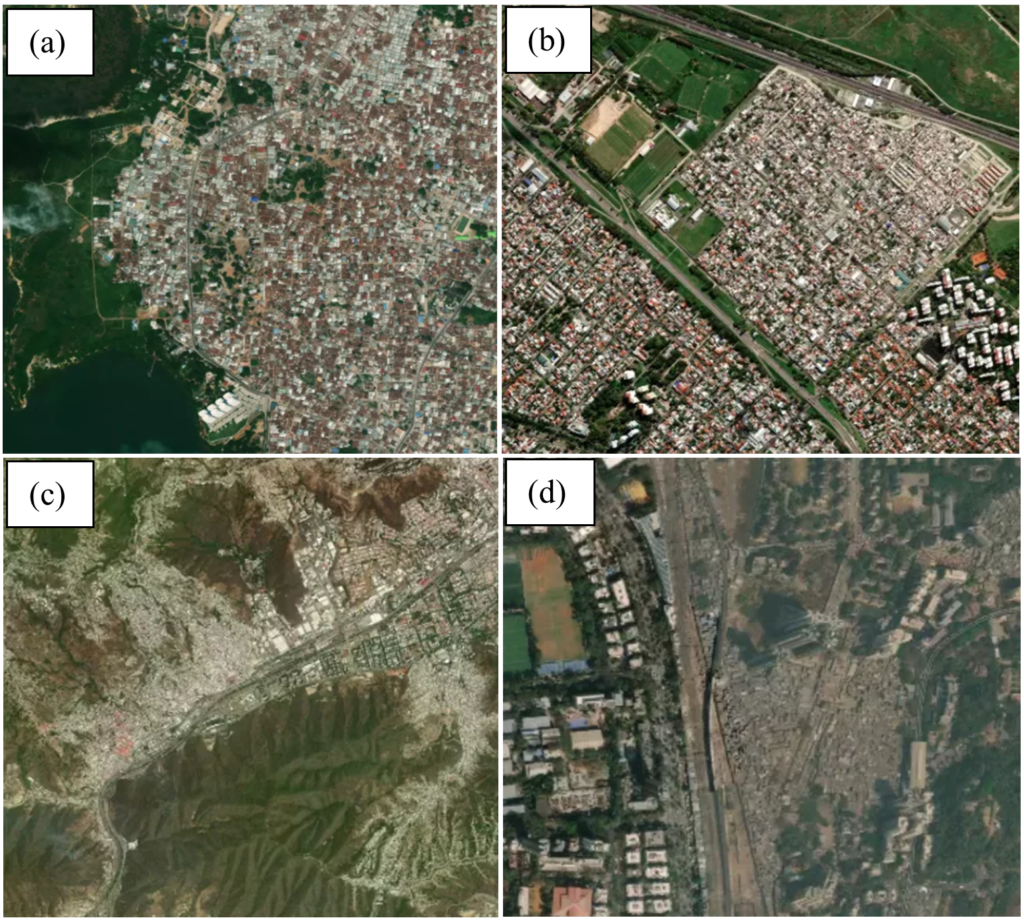

Advances in remote sensing are helping to tackle some of these conceptual snags. Machine learning, object-based approaches, pixel-bases approaches, visual image interpretation, and statistical modeling have all been successfully used to identify these communities from satellite imagery. High-resolution data on population, land cover, healthcare access, building density, literacy, and even event locations of armed conflict are helping researchers (such as the IDEAMAPS Network) define new frameworks based on domains of deprivation.11,12 Members of these communities have been more engaged than ever in these projects through the efforts of advocacy organizations like Slumdwellers International (SDI), which has used its extensive network of grassroots community organizations to profile over 7,712 slums in over 224 cities using participatory mapping methods. SDI’s profiles include data on infrastructure provision, level of community organization, health access, transportation availability, as well as a history of the community.

While these approaches have made great progress in advancing a more nuanced debate on what I will call urban informality, data scarcity is still an issue. Morphological differences in urban informality between cities and regions (and even intracity) make the task of developing a global database of urban informality technically daunting. Participatory approaches, despite providing rich, detailed data, are time-consuming and resource intensive. As a result, most studies researching urban informality adopt a case study approach which precludes interregional, macro-level analyses.

As one attempt to address this data gap, I, with the help of Caroline Kersey at Virginia Tech, reached out to nearly 90 research groups that have published work using remote sensing methods to identify and classify urban informality. Through these efforts, we have gathered geospatial datasets identifying areas of urban informality in 28 cities across the Caribbean, Central America, South America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Asia Pacific. To visualize the data, Dag Yeshiwas at WireWheel supported the creation of an AWS S3 static website hosting an interactive, high-resolution satellite basemap using Mapbox API, which is available at www.mappingurbaninformality.com. In the interest of open science, the data is freely available for use on a Github repository where authors have consented to licensing their datasets to the public domain.

Urbanization will continue to be a megatrend that defines the material conditions and quality of life for billions in the Global South in the decades to come. These are precisely the same populations expected to experience the most severe climactic impacts of climate change, and which have the least adaptive capacity. The task of imbuing the cities of tomorrow with the social, economic, and technical resilience to withstand these impending shocks and stresses is enormous, and urgently calls for improved geospatial tools and richer data. While this dataset does not solve the conceptual challenge of understanding and labeling the dynamics and diversity of urban informality worldwide, it does provide us a useful analytical resource with which to make meaningful interregional comparisons. In the coming months, I plan to leverage this dataset to help understand the impacts of climate risks – such as more frequent and intense storms, irregular precipitation, landslides, and sea level rise, among others – on informal urban communities in the hopes that this project may be of service in advancing such an integrated approach to urban resilience for researchers and practitioners tackling the challenges of urban informality, infrastructure provision, and climate adaptation.

References

| [1] | D. Hoornweg and M. Freire, “Building Sustainability in an Urbanizing World,” World Bank, Washington, DC, 2010. |

| [2] | P. Jones, “Formalizing the Informal: Understanding the Position of Informal Settlements and Slums in Sustainable Urbanization Policies and Strategies in Bandung, Indonesia,” Sustainability, vol. 9, p. 1436, 8 2017. |

| [3] | United Nations Statistics Division, “SDG 11: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable,” [Online]. Available: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/goal-11/. |

| [4] | United Nations, “Millenium Development Goals Indicators. Indicator 7.10 Proportion of Urban Population Living in Slums.,” 2015. |

| [5] | United Nations, “Report of the UN Economist Network for the UN 75th Anniversary: Shaping the Trends of Our Time,” 2020. |

| [6] | UN-Habitat, “Urbanization and Development: Emerging Futures,” Nairobi, 2016. |

| [7] | UN-Habitat, “State of the World’s Cities 2010/2011: Bridging the Urban Divide,” London, 2008. |

| [8] | United Nations Human Settlement Program, The Challenge of Slums, Taylor & Francis Ltd, 2003. |

| [9] | M. Adler-Gillies, “‘Slum’ label doesn’t belong in the language of social reform, author argues,” ABC News, 6 October 2017. |

| [10] | D. Biller and K. Petroff, “In Brazil’s Favelas, a Middle Class Arises,” Bloomberg, 20 December 2012. |

| [11] | IDEAMAPS, “IDEAMAPS Data Release,” 2020. |

| [12] | D. R. Thomson, A. Shonowo, A. A. Imizcoz, N. Rothwell and M. Kuffer, “What defines urban deprivation?: Domains of Deprivation Framework v1,” 2020. |